Analytical approach enables a potential buyer to stand apart from the crowd and to give its offer a real competitive edge.

Forward

Two common obstacles have prevented many an acquisition from being successfully negotiated. One is inability to settle on a realistic price. The other is failure to “sell the seller” on the nonfinancial aspects of the merger. But, say these authors, these snags can be overcome: “By first analyzing, and then graphically portraying, the key relationships of various financial alternatives, management should be able to grasp the trade-offs involved and the limitations of various price levels and terms. This approach, combined with a solid plan for the growth of the combined businesses, should result in a deal."

Mr. MacDougal has been a Partner in McKinsey & Company’s Los Angeles office, where he was extensively involved in merger and acquisition work. Recently, he became Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer of Clayton Mark & Company, a manufacturer of specialized industrial products. Mr. Malek is currently the Deputy Undersecretary of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Previously, he was co-chief executive officer of Triangle Corporation, a manufacturer of hardware supplies, and associated with McKinsey & Company, specializing in mergers and acquisitions.

Mergers and acquisitions still moon large in most companies’ strategic growth plans. The pressures to acquire—whether to improve earnings growth and stability through diversification or to ward off possible take-overs—preoccupy chief executives as well as staff planners. Very often, these pressures demand large amounts of presidential time.

If the top executive’s background happens to be in corporate finance, this may be time well spent. But more often he will have come up through the sales or manufacturing ranks perhaps with a tour of duty as a division manager.

Such cases, when the chief executive is not well prepared by experience for his vital role in acquisition analysis and negotiations,and negotiations, often follow a familiar pattern. Much effort goes into screening long lists of industries and companies, and into gathering published data on possible acquisition candidates, but not enough thought is given to developing an analytical approach to merger negotiations that can be understood and communicated effectively.

Two kinds of consequences may result: (a) through failure to “sell the seller” on some aspect of the acquisition, management may find itself unable to “close” or complete anything of substance. Or, worse yet, (b) faulty financial analysis may lead management to acquire a poor company, or to pay so much for a good one that it cannot hope to earn an acceptable return on the investment.

The approach to acquisition negotiations outlined in this article is designed to enhance the chances of success in merger negotiations. It shows negotiating executives, too often perplexed by the maze of technical, legal, and financial details surrounding a prospective acquisition, how to handle three critical aspects of the negotiating process:

| 1. |

Laying the groundwork by understanding the financial relationships that underlie any agreement between the two companies. |

| 2. |

Developing the seller’s interest in the non-financial aspects of the proposition. |

| 3. |

Resolving the financial facts in a way that will make possible an early and realistic agreement on terms. |

Laying the groundwork

As the first step toward successful acquisition negotiations, the acquiring company should lay the groundwork in two areas: (a) it needs to think out carefully and express in specific terms its own corporate objectives and acquisition criteria; and (b) it needs to study and understand the basic financial relationships between itself and its potential acquisition.

Objectives and criteria

Developing corporate objectives and acquisition criteria is too important and complex a subject to be covered thoroughly here. At a minimum, for acquisition evaluation purposes, corporate objectives should include such financial standards as earnings per share growth rate and annual return on investment. Without these yard sticks, there is no way of knowing whether a given acquisition would act as a spur or brake on overall corporate performance. Consider:

- An acquisition candidate that is showing an earnings per share growth rate of 9% a year compounded will look very good to a company that is currently growing at 5.5% a year compounded and aiming for an 8% growth rate.

- However, that same acquisition candidate will (or should) hold little attraction for a would-be acquirer that is growing at 10% a year, and has set its sights on 14%.

The earnings growth rate and return on investment an acquirer should set as its goals depend on many factors that will emerge only from a thoughtful evaluation of internal corporate potential combined with a sound assessment of the business environment. Some companies regularly measure themselves on two counts: first, against their own industry; then, against a cross section of all manufacturing companies, such as that provided by Fortune’s “500.”

For example, an earnings per share growth rate of 12.5% a year compounded would equal the performance of companies at the bottom of the top quartile of Fortune’s “500” during the past decade. A 15% return on shareholders’ equity would also place a company at the bottom of the top quartile during this period. The end result should be performance goals that are challenging but attainable.

Criteria for the evaluation of investments should include, in addition to the type and size of business and other appropriate screening factors, a return on investment (ROI) target that takes present-value considerations into account. The discounted cash flow method provides a good measurement of the return on investment. A typical company, then, might develop these yardsticks against which to measure prospective acquisitions:

| 1. |

Annual compound earnings per share (EPS) growth rate. |

| 2. |

Annual return on shareholders’ equity. |

| 3. |

Prospective return on the investment, calculated on a discounted cash flow basis. |

The buying company can then proceed to examine the financial characteristics of the acquisition candidate, evaluate them in the light of the corporate objectives and acquisition criteria it has established, and begin to define the range of feasible purchase prices and terms.

Prenegotiation homework

Once the buying company has spotted a promising acquisition candidate, has become acquainted with its principal characteristics, and is preparing for the first approach, the time has come to examine certain key relationships in order to determine what price can be paid—and in what form—without undermining corporate objectives. Management should at this point determine:

- The relationships of various selling company EPS growth rates and new capital requirements to possible purchase prices and discounted cash flow ROI.

- The impact that various earnings-growth rates of the acquisition candidate and various purchase prices and forms of payment will have on the parent company’s earnings per share and annual ROI.

- The maximum percentage of control the acquired company would retain at various purchase prices and under alternative forms of payment.

To determine these relationships, we recommend an analytical approach that has proven effective in practice and is relatively easy to use. A series of graphic guides such as those used in the accompanying simulated case history

(see Exhibits I through VII) will quickly demonstrate the financial considerations involved in most acquisitions.

The graphs make it simpler for negotiating executives to grasp the essentials before talks begin. They provide a sound understanding of the true trade-offs involved and the limitations on purchase price and terms.

br /> Management can thus proceed into negotiations with greater confidence, since the graphs can be used for a quick assessment of the potential impact of changes in terms or prices. This increased flexibility helps to eliminate unnecessary roadblocks and prevent mistakes.

Finally, as we shall see, the graphs themselves become persuasive tools for the acquiring company’s negotiating team: when shown to the seller, they help in moving talks on the crucial financial details from an emotional or intuitive level to a more objective plane where the facts convincingly speak for themselves.

Simulated case history

How does this analytical approach work in practice? We have devised an example to illustrate both the financial analysis which management of the acquiring company should undertake and the graphic guides it could use as tools.

Synergetics Corporation, a publicly owned (NYSE) company with $125 million in sales, is preparing to commence negotiations with Historic Family Enterprise (HFE), a $12 million company closely held by the chairman of the board and his family. To provide a framework for its acquisition program, Synergetics’ board of directors has approved these corporate financial objectives and acquisition criteria:

1. All new capital investments, including acquisitions, must provide a discounted cash flow ROI of 12% or better after taxes.

2. The objective for Synergetics’ earnings per share growth is 10% a year.

3. The target for Synergetics' annual return on shareholders’ investment is 14%.

4. Dilution of earnings per share should be minimized, and any dilution which does result should be eliminated by the third year after acquisition.

The basic financial characteristics of Synergetics and of HFE look like this (HFE’s earnings per share are not known, and there is no established market value for HFE’s stock):

| |

|

Synergetics Corporation |

|

Historic Family Enterprise |

|

| Profits after taxes |

|

$5,000,000 |

|

$1,000,000 |

|

| Earnings per share |

|

$5 |

|

- |

|

| Past growth rate |

|

6% |

|

10% |

|

| Management growth projection |

|

6% |

|

12% |

|

| P/E ratio |

|

12 |

|

- |

|

In preparing for negotiations, Synergetics’ management has two purposes in mind: (a) to understand the financial relationships that will exist between the two companies so that it will know what prices are reasonable under varying conditions—and why—and (b) to improve its ability to communicate purchase –price limits which the HFE negotiating team will understand and consider reasonable.

At this point, Synergetics’ executives must clarify the basic financial issues. Because HFE is not publicly owned, there is no established market price, nor has HFE management indicated a preference for any particular exchange instrument. In addition, Synergetics is uncertain what rate of earnings growth to expect from HFE. Therefore, Synergetics is interested in analyzing these financial impacts:

- The relationship among probable HFE earnings per share growth rates, purchase-price levels, and Synergetics’ discounted cash flow return (e.g., with an HFE annual growth rate of 15%, what is the maximum feasible purchase price if the discounted cash flow ROI is to equal 12% or better).

- The year-by-year impact on Synergetics’ earnings per share of various HFE growth rates and purchase prices (e.g, at what growth rate is dilution overcome within three years if HFE is purchases for $20 million in common stock).

- At a given price, the year-by-year effect on earnings per share of alternate combinations of cash, common stock, and preferred stock (e.g., if the purchase price is $20 million, what is the effect on dilution of increasing the cash portion from 5% to 20%).

- The relationship of purchase price and type of exchange instrument to the resulting degree of HFE control (e.g., if the price is $20 million and the terms are 25% cash and 75% common stock, what percentage of the new, combined enterprise will be represented by former HFE shareholders).

Assessing ROI target

Discounted cash flow return analysis, now in use by a number of sophisticated companies, offers several important advantages. For one thing, it provides a means of determining value that is independent of the financial terms involved. If only EPS impact is measured, an all cash acquisition of a slowly growing company, for example, can be made to look good on a straight earnings per share basis because the effect of leveraging the company, through the use of cash, is confused with the acquisition evaluation.

For another thing, the present-value ROI approach also gives full recognition to the fact that earnings received in, say, ten years are less valuable than those received in two, three, or four years. In addition, management can easily decide by assessing the ROI in terms of present value whether acquiring a given company is preferable to using the same capital for internal projects or for other acquisitions.

The essence of this discounted cash flow ROI approach is to estimate cash inflows for each year of a given period (often a ten-year period is appropriate). These inflows include the capitalized increases in earnings per share. In addition, cash outflows are estimated for the same period—outflows which include the initial purchase price of the acquisition and the amount by which capital investment exceeds depreciation. The initial value of the company acquired is then treated as a cash inflow in the final year of the period under consideration.

In the case of the Synergetics Corporation, assume that management’s calculations show that investing new capital at a discounted cash flow ROI rate of 12% or better will produce an annual return on shareholders’ equity of 14% or better—thus meeting two of the goals approved by Synergetics’ board of directors. (Note that the 12% discounted cash flow is on total capital, whereas the 14% return on shareholders’ equity covers only the equity portion.)

Therefore, in contemplating the purchase of HFE, the first task for Synergetics’ executives is to project a range of possible compound after- tax earnings per share growth rates for HFE, and then to ask:

What is the maximum price we can pay at each of the various HFE growth levels if we are going to meet our 12% discounted cash flow ROI target?

Exhibit I shows graphically this relationship between purchase price, projected HFE growth rate, and Synergetics’ return on investment. (See Appendix which describes in detail the assumptions underlying this exhibit. A financial analyst familiar with basic present-value techniques can easily construct a similar chart.)

If an annual HFE growth rate of 10% seems probable, then Synergetics’ can pay $20.75 million for the company and get a 12% return on investment. However, if HFE is expected to grow at a rate of 12% annually, a price as high as $25.25 million can be paid without falling below the ROI criterion set by Synergetics’ board of directors.

Synergetics’ management, therefore, knows that negotiations on the purchase price should stay within a range of $20 million to $25 million, and that the critical factor is the HFE projected earnings per share growth rate.

Effect on earnings

A second question now confronts Synergetics’ executives:

If we are to overcome dilution within three years, as our acquisition criteria specify, what is the appropriate purchase price, and should it be cash, common stock, preferred stock, or some combination of these?

Using the range of estimated HFE growth rates, Synergetics’ executives decide to test the effect of offering a $20 million exchange of Synergetics common stock for HFE common stock to determine both the impact on combined earnings per share and the year in which dilution can be replaced by appreciation

It is immediately apparent from Exhibit II that even if HFE were to grow at a rate of 15% annually, Synergetics’ earnings would be diluted through the sixth year after acquisition with a $20 million common-for-common exchange. Lower HFE growth rates continue the dilution even longer. In other words, a common-for-common exchange at this price rules out hope of meeting Synergetics’ acquisition criteria.

Synergetics’ management then must work out purchase terms and a price that will allow dilution to be overcome by the third year. Again, various HFE projected growth rates—of 10%, 12%, and 15% per year—are evaluated.

As Exhibit III indicates, if dilution beyond the third year is to be avoided, the top price Synergetics can offer HFE in a common-for-common exchange, assuming a projected HFE growth rate of 15% a year, is $15.32 million. With a more probable 12% growth rate, no more than $14.16 million in common stock can be paid.

Synergetics knows that the owners of HFE would consider a $15.32 million offer quite unrealistic. It would represent only slightly over 15 times HFE’s annual $1 million after-tax earnings, and comparable companies in HFE’s industry have been selling for 18 times earnings—which suggest what HFE’s expectations will be. The average price for all companies acquired in the past few years has been in the range of 23 to 25 times earnings.

With a modest 6% annual growth rate, Synergetics itself commands a price/earnings ratio of 12: HFE’s growth rate is expected to be nearly twice that of Synergetics. Thus, if the negotiations are to succeed, it is apparent that Synergetics will have to put forth a better offer. The key question at this point then becomes:

Is there any combination of exchange instruments that will make a $20 million purchase price consistent with Synergetics’ own objectives?

As Exhibit IV shows, the introduction of cash into the acquisition package substantially affects the impact of the acquisition on Synergetics earnings per share. Assuming that the 12% projected growth rate for HFE is most likely, paying about 50% of a $20 million purchase price in cash will produce neither dilution nor appreciation within three years.

Exhibit V, which covers a broader range, indicates the various purchase prices and the various mixes of cash and common stock that could start earnings per share appreciation after the third year. This exhibit shows that if Synergetics wants to keep the cash input of the package below 50% for tax purposes, then its offer cannot go above $20 million.

Exhibit VI illustrates a similar family of curves, developed to show the results of various combinations of cash and preferred stock. Given a $20 million purchase price of 40% cash and 60% convertible preferred, EPS appreciation will begin in the fourth year, after conversion of the preferred.

By this time, Synergetics’ management realizes that it must use a fairly high percentage of cash and/or preferred stock to effect a deal that meets its criteria for acquisitions. During the negotiations ahead, the charts will help its team to move quickly from discussion of one financial instrument and one purchase price to an alternative, keeping a clear view of what the effect of each would be on corporate objectives.

Impact on control

Since HFE is a closely held company, the degree of control that HFE shareholders can exert after the transaction becomes especially important. Hence the natural question for Synergetics’ management is:

What combinations of cash and stock would give HFE shareholders too much control of Synergetics and at what purchase price would this occur?

Exhibit VII illustrates how Synergetics improves its own control as the purchase prices is reduced and the percentage of cash or of preferred stock in the package is increased. This is the only exhibit of the series which Synergetics’ management would do well to keep to itself.

As we shall subsequently see in the final section of this article, Exhibits I through VI can—and should—be shown to HFE’s management when discussion of the financial terms begins. Actual experience has shown that charts such as these become a useful negotiating tool which help to guide both parties toward a reasonable and satisfactory agreement.

Developing seller interest

Having established the basic financial relationships which underlie the acquisition, Synergetics’ management must now turn its attention to other aspects of the coming discussions, with an eye toward the errors that so often result in unsuccessful negotiations.

It is not unusual to see a would-be buyer approach a company he knows is for sale—often with his investment banker in tow—and devote most of his time to discussing purchase prices, terms, and the financial advantages that selling shareholders can expect. By doing this he implicitly overlooks a major fact of life in today’s merger conscious business world: any attractive company known to be interested in selling (and most that are not interested) will have four or five—perhaps even dozens—of offers. Most of these will be reasonably attractive financially, with several offering to exchange securities which promise comparably attractive growth prospects.

In a situation like this, the prize often goes to the company that can offer the seller something more than money: a sound future for the business to which he has devoted years of hard work and personal commitment.

Both owners and managers of a selling company are normally extremely concerned about the future of their enterprise, whether or not they retain a continuing stock interest. Even if management does not hold substantial shares, the owners will feel a personal obligation to their executives and will usually want their support in any merger or sale.

In most cases, the buying company itself will hope to keep on the acquired company’s management after the deal is closed. The would-be buyer who can arouse the seller’s interest in the nonfinancial aspects of the acquisition has won an advantage that sets his company apart from the crowd of aspirants. This entails considerable work even before the negotiations commence.

To begin with, management of the acquiring company should gain a thorough understanding of the seller’s business and industry. Elementary as this point may seem, executives of a would-be purchaser often enter negotiations armed with only the sketchiest knowledge of conditions in the business their company is seeking to enter. In such cases, it is not unusual for the seller to call off the deal before it really gets started.

Once the negotiators have familiarized themselves with the selling company’s background, they must work out a strategy to activate the seller’s strong, though sometimes latent, interest in the nonfinancial aspects of the merger. The key tasks at this point are:

- To identify, and then communicate, specific business advantages from which the selling company can benefit after the acquisition.

- To map out a thoughtful and stimulating growth plan for the new combined enterprise.

- To develop sound and continuing personal relationships.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Each of these factors will vary in importance according to the situation, but all of them should be completely thought through during the initial planning for negotiations and refined as discussions progress.

Identifying specific advantages

There is no “cookbook” approach to help the buyer spot business advantages that will interest the selling company. The characteristics of the selling company itself and of the field in which it operates are all-important. For example, a highly fragmented industry in which there are numerous single-product manufacturers serving the same market offers the chance to present telling sales economies:

These are but a few examples of the business advantages a buying company should seek to develop. The essential thing to remember is that in most good companies top management is vitally interested in such goals as improving competitive position, capitalizing on new market opportunities, and investigating other major growth possibilities. A merger is likely to make substantially more sense to these men, regardless of the purchase price, if it means they can achieve one or more of their primary objectives.

In each case, executives of the buying company should do their homework, thoroughly exploring the advantages they can offer, and then, early in the negotiations, beginning to work with the potential seller to determine their value. Discussing such opportunities in itself helps to form a strong link between the two companies during the period when they are getting to know one another.

Mapping combined growth

Before negotiations begin, management of the buying company should develop a preliminary growth plan for the new, combined enterprise based on careful research into the seller’s business and industry. Nothing will cause the selling company to lose interest faster than a naïve, superficial growth plan that overlooks important industry factors.

What should be presented—again, early in the negotiations—is a thoughtful, fact-founded plan, in writing, which is considered a preliminary suggestion. Executives of the acquisition candidate should be asked to contribute their ideas. Participation in further development of the plan will strengthen their interest in seeing that the negotiations succeed. A combined growth plan might include:

1. A statement of corporate goals for the new enterprise – to convince the seller that the combined company is really going to move ahead and achieve something that would not be possible for either company alone. (As these goals are considered, the discussion focuses on the months and years ahead. Small current differences in specific financial terms then tend to become less important.)

2. A joint marketing program- to capitalize on existing economic trends. (The emphasis should be on using the combined resources, financial and otherwise, of the two companies.)

3. A tentative program for further acquititions in the same or allied fields—to utilize the selling company as the building block.

4. A thoughtful organization philosophy—to include the reporting relationship of the selling company, compensation arrangements for its top executives, employment contracts, and director representation.

The acquiring company’s management should think through these organizational questions prior to the negotiations and raise them early in the sessions. They are matters of great concern to the selling company’s owners and managers, but are often awkward for them to bring up without appearing more interested in the acquisition than they would like to admit.

A word of caution in the organizational and compensation area: although these points should be touched on early in the discussions, it is unwise to dwell on them then lest the acquiring company be accused of attempting to “buy” the seller’s top executives. This was what happened when Crane Corporation tries to take over Westinghouse Air Brake, and it became an important factor in WABCO’s defense against Crane.

An illustrative example shows a situation in which an effective combined growth plan had an appeal as important as the financial considerations. In the actual negotiations, this plan was spelled out in considerable detail, with financial objectives, organizational structure, and other essential elements carefully described.

Consider:

Cyprus Mines Corporation, a Los Angeles-based mining company, approached Sierra Talc and Chemical Company, the nation’s largest talc producer, with the idea of combining the resources of various mineral companies into a single organization.

At the time, the industry was composed of numerous companies, each producing and marketing a single mineral—clay, talc, calcium carbonite, feldspar, and so on—to the same customers, primarily in the paint, paper, rubber, and plastics industries. Few of the existing mineral companies were large enough to afford direct-sales representation, industrial-technical representative specialization, or funds for research which could identify new uses for their products.

Sierra like the Cyprus plan for combining many single-product companies, and agreed to sell for CMC common stock. The combined growth plan also appealed to one of the largest clay companies in the nation, United Clay Mines, which soon joined the new group. Other companies followed, and now the United Sierra Division of Cyprus Mines Corporation has a complete national direct-sales force, supported by industry specialists, and a research program for new minerals applications that none of the individual companies could have afforded.

An exciting growth plan demonstrates the potential for increased earnings per share and the creation of added value. This is particularly meaningful where an exchange of stock is contemplated. Equally significant, in all cases, the plan can offer a more stimulating environment and broader horizons to the sellers’ executives.

Advancing an explicit growth plan can be especially important when the company in question is “not for sale” and therefore no financial pressures can be applied. In such a case, an imaginative, strong growth plan may be the only reason for it even to consider a merger.

Building personal relationships

Even when all business interests interlock and the financial terms are acceptable, a surprising number of acquisitions fail to mature because the buying company overlooks the importance of the “personal touch.” Particularly when large corporations are involved, it is easy to think that the financial terms, the compelling logic of a sound plan, and the business advantages are all that count. Yet there are enough examples from recent years when the success or failure of the negotiations depended on personal relationships for even the most rigidly analytical manager to take them into account.

Not surprisingly, the chief executive officer of the acquiring company plays the most vital role in developing effective personal contact with the seller. Many people who own, or who are in a position to influence the sale of, a company are already independently wealthy. A feeling for “their kind of people” can be the determining factor when they come to decide on a long-term relationship.

It is particularly important that the acquiring company’s chief executive officer participates in the initial discussions and maintains close contact with the principals as the negotiations proceed, not only to demonstrate his sincere intentions but also to offer concrete evidence of the seller’s importance to the buying company’s plans. For example:

Not long ago, a senior vice president and director of a large West Coast company approached the president and chief executive officer of an East Coast capital goods manufacturer. The aspiring buyer’s vice president was startled when the president of the company he had contacted failed to return his phone call; surely the president of the acquisition candidate had an obligation to shareholders to consider any offers made in good faith. Serious discussions never began, and communications between the two companies were both rare and unusually awkward.

Several months later, through an investment banker, the senior vice president discovered that the president of the East Coast company had, in fact, been talking about selling with a number of other large corporations. Why had he spurned the advances of the West Coast company? In his own words, “If the chairman or the president does not think it worth his while to come and talk to me, then I can’t see any future in our trying to work together.”

If discussions between the companies take place in large, formal sessions with a rigid agenda, it is impossible to develop any kind of personal rapport. Informal contacts should be encouraged –even though they may involve nothing more profound than a common interest in freshwater fishing

In addition, the selling company’s management should be introduced to satisfied executives of other companies which have been acquired. George Scharffenberger of City Investing, an active buyer in recent years, states that this approach is a primary reason for City Investing’s success in acquisition. North American Rockwell also uses this approach extensively.

Once negotiations are under way, no week should pass without some casual discussion—by phone or in person—between the two chief executive officers. This regular contact can act as a sort of safety valve which prevents misunderstandings from building up to the point where a serious disruption in negotiations could occur. Although this strategy may seem obvious, it is frequently overlooked and serious misunderstandings often develop during the long, silent periods.

Although the chief executive officer of the acquiring company should keep in close touch with his counterpart, this does not mean that another competent senior executive cannot take over the major role in actual negotiations. What is important is that the seller feel free to contact the buyer’s chief executive officer as often as he pleases. It is also vital that the senior executive in charge of day-to-day talks be given adequate authority, since nothing can cool negotiations more quickly than to send a representative who must continually obtain his chief executive officer’s approval before he makes a commitment.

Resolving financial terms

By the time discussions begin to evolve into true negotiations, there should be an atmosphere of warm goodwill between the executives of the buying and selling companies. The problem then is to be able to resolve financial terms in a way that allows the economic considerations to be communicated without diminishing this goodwill.

It is at this point that charts such as those used to illustrate the Synergetics-HFE case history (Exhibits I through VI) can be shown to the seller and become effective negotiating tools. The buyer can use them to elicit initial reactions without actually proposing a price, knowing that they are concrete evidence of the acquiring company’s thoughtful approach to the future. As such, they inspire a sense of respect for management’s preparation and thoroughness.

The acquisition prospect can readily accept the logic of the buyer’s need to obtain a return on investment equivalent to its target rate. The desire to avoid earnings dilution is equally understandable. In thus introducing a discussion of such basic financial relationships at an early stage in the talks, the acquiring company tends to appeal to the candidate’s common sense and good judgment. In this way, the discussions can be based on objective considerations, and emotions cannot so easily enter.

Perhaps even more important – as actual experience has shown – is that by demonstrating clearly the financial relationships, and thus “opening the book” to the candidate, the acquiring company creates a feeling of mutual trust and understanding. Again, the focus is on the future and on the success of the new, combined enterprise which, by now, both the buying company and the seller can begin to see as a reality.

Conclusion

Our experience indicates that the approach to merger negotiations outlined in this article offers a good way of surmounting the two most common obstacles to success: inability to settle on a realistic price, and failure to “sell the seller” on the nonfinancial aspects of the acquisition. By first analyzing, then portraying graphically, the key relationships of various financial alternatives, management cannot fail to gain a solid grasp of the true trade-offs involved and the limitations of various purchase-price levels and terms.

Equipped with this understanding, executives can go into negotiations knowing that they can quickly assess the impact of alternative prices, financing methods, and growth rate projections on the ROI and EPS performance of their company. This greater flexibility helps to eliminate unnecessary roadblocks, prevent mistakes, and increase the chances of a successful acquisition. Finally, the charts that are developed provide an excellent basis for fact-founded “open-book” discussion during the negotiations.

Persuading the selling company of the non-financial advantages of the acquisition will not, of course, be accomplished through good quantitative analysis or well-designed charts. But there are at least three steps a potential acquirer can take to set itself apart from the crowd in the seller’s eyes and give its offer a genuine competitive advantage:

1. It can learn more about the seller’s business than other prospective acquirers, and thus identify specific business advantages and bring them into the negotiation discussions.

2. It can develop a combined growth plan that will capture the imagination of the seller and lessen the likelihood of major disagreements arising over minor terms of the agreement.

3. By increasing the chief executive’s personal involvement and ensuring frequent informal contacts with executives of the acquisition candidate, it can develop the sound personal rapport that is prerequisite to a successful working relationship.

Admittedly, negotiation is not a science but an art. However, technical advances are possible in art as well as in science. Our experience indicates that an analytical approach to merger negotiations can materially improve any acquirer’s prospects of success.

Appendix: Notes to Exhibit I

In this exhibit, ROI on a discounted cash flow basis is used to evaluate the proposed acquisition. Any advantages which would result from new business opportunities are not included in the calculations. At a later point in the negotiations these can be taken into account by including any profit improvement in the performance of the company to be acquired.

It is also assumed that the candidate company will generate its projected earnings without additional capital investment from the parent: the only investment is the purchase price. Additional investment, however, can be included as a cash outflow if appropriate.

The principal inflow to the parent company consists of the assumed annual incremental increase (or decrease) in the total value of the candidate company. By including these changes in company value in the cash flow, traditional cash flow analysis is extended to include potential returns, even though the choice can be made not to realize them as they occur.

The total value of the candidate is assumed to be earnings after taxes multiplied by the P/E ratio typical for its industry. The P/E ratio must be estimated for future years; in this exhibit it is assumed to be constant during the next ten years and equal to the present industry P/E of 18.

Assuming that the candidate company is sold at the end of a ten-year period (the limit for a reasonable projection), the value of the potential return in the last year is calculated as the increase in value for that year plus the market value of the company at the time of purchase.

On this basis, the discount rate at which the present value of these inflows is equal to a given purchase price is the rate of return for the total investment.

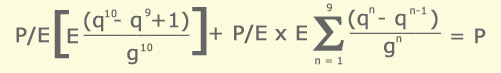

To construct this chart, let the present profit of the company to be evaluated ($1 million in Exhibit I) grow at alternative growth rates (8%, 9%, 10%, 11%, 12%, and 13% in Exhibit I) over a period of ten years. Calculate the increments and multiply with the average industry P/E ratio (18 in Exhibit I). Add to the tenth value the average market value in year 0, i.e., average industry P/E ratio times earnings in year 0. Then calculate the present value (purchase price) for various hypothetical rates of return. This can be expressed in the following equation:

where:

P/E = average industry P/E ratio

E = earnings in year 0

P = purchase price

q = 1 + growth rate / 100

g = 1 + rate of return / 100

Negotiating a satisfactory conclusion

Meshulam Riklis,

“Expansion Through Financial Management,” in the The Business of Acquisitions and Mergers, edited by G. Scott Hutchinson, New York, Presidents Publishing House, Inc. 1968, p. 178.

Negotiations take place between human beings, each having his own problems and his own ways. No deal can be successfully consummated without adjusting the terms to fit the seller’s needs and the answers to his specific problems, as well as taking into account the fact that he will habitually be surrounded by “experts” and “advisers” who must also be convinced of the seller’s benefits from the transaction. A negotiator must be able to analyze objectively the terms from the standpoint of the opposing team and all through the negotiation act with complete self-control. He must be neither jealous of any benefits gained by the seller, nor begrudge him any concessions agreed on if he is to achieve the outcome he has in mind.

Acquisitions and mergers may serve several purposes, but they usually have one single objective at the start – namely, to create a better and more rounded operation that can lead to more profitable results…

Profit motivation should of course be the main consideration. Without this, I would question the wisdom of the whole transaction.